“The heart has its reasons of which reason knows not.” In one eloquent blow, the 17th century scientist and philosopher Blaise Pascal both vindicated emotion and revealed the failure of reason.

After a lifetime of studying the heart and at the risk of sounding somewhat arrogant, I think I’ve caught a glimpse of the heart’s reason.

I must give tribute to the conceptual glasses I have been privileged to wear. The attachment and developmental lenses so brilliantly honed by inquiring minds from the past have turned out to provide almost X-ray vision to the workings of the mind and even predict the discoveries of neuroscience. Perhaps it is the fact that these lenses were constructed with utmost regard to all things natural.

Age seems to have clarifying effect. I can see much clearer now that the details are finally dimming from view. It is rather ironic that the less I can remember, the better I seem to see. Distance also seems to make a difference. Like those works of art that only reveal their truth when standing far enough away from them, my grandchildren are able to teach me lessons now that I was far too close to my own children to comprehend.

So I think I’ve got it! I’m much too shy to run naked through the streets yelling ‘Eureka.’ And I didn’t think of this while in the bath as did Archimedes. But nevertheless I believe I’ve got a glimpse of the inner logic of the limbic brain. I don’t just mean that togetherness is the ultimate mammalian endeavour. This realization has been clear for some time now – that survival for mammals lies in their ability to preserve proximity with others. In other words, babies don’t seek to survive; they seek to be close. And we are all just big babies at heart. That realization is absolutely basic and pivotal to making sense of emotion.

What truly has hit me like a ton of conceptual bricks is the logical extension of this remarkable discovery – that separation is the fundamental problem for the limbic brain to solve. Simple enough – and self-evident once seen. However, this dawning realization has taken years to truly sink in. Maybe the problem has been that separation itself is so blinding; it is rather akin to looking directly at the sun to discern its character. As the artist-of-nature Emily Carr once observed, truth sometimes has difficulty revealing itself when we are looking at it too directly.

If I’ve got it right about the heart, then our most popular parenting practices are misinformed and our school system is misguided. If this is truly the task of the limbic brain, then it makes sense why anxiety and bullying are on the rise and why empathy is on the wane.

If fixing the separation problem is the heart’s modus operandi, we have an explanation for such diverse phenomena as love, neuroses and the shape of the digital revolution. We also have an answer for why our most favoured instant solutions to the separation problem (being good, being esteemed, digital connection, fantasized intimacy, and even winning) get in the way of the ultimate developmental answers.

If I am seeing correctly, then we have a basic guiding principle to a multitude of parenting challenges including the handling of bedtime, divorce, discipline, daycare, school and even death. We also have the common denominator to most childhood problems and the way through to a singular solution.

I feel somewhat like I do when the theme of a book or a movie is not revealed until near the end. I am compelled to start once again from the beginning, armed with the insight that would make all things look different and be the tie that binds every detail together. Of course I cannot do this in real life except via reflection, which I yearn for now more than ever. I also find myself wanting to study anthropology, culture, religion and mythology. The boundaries between disciplines begin to blur when the dots are joined and the big picture has emerged.

It will be rather daunting to tackle this subject in the time allotted for a keynote. What I would most like to do is share my awe. I think music would be the best way but I would have to start all over again to master that medium. I promise I won’t sing or lead an orchestra, but I do hope that I will be able to share a bit of what I see.

Dr. Neufeld will articulate his theory on How to Stay Close When Apart in a two-part keynote address that he will present at the Seventh Annual Vancouver Neufeld Conference on Saturday, May 2, 2015. For conference details and to register, please visit our events page.

The New Year is traditionally a time for resolutions. In years past I have repeatedly resolved to spend more time with my children; to exercise more and eat better; to have a clean house. I have always struggled with these resolutions and this year I finally stumbled on the reason why. It is the word resolution. Defined as “a firm decision to do or not do something,” it does not leave much wiggle room. Resolute sounds strong and determined – and final.

In my case it also seemed to be about the act of re-solving – trying to solve the same problem again, and again, and again. I lived my life for many years resolving, every Monday, to eat better; by Wednesday my resolve disappeared and I had to wait until Monday to start the cycle again. If I broke the rule, I had to start over from scratch – and over and over. But I never got anywhere. Resolving never worked for me. Perhaps because when it becomes about doing it right, it paralyzes me with the threat of doing it wrong. It becomes black and white, all or nothing. What happens if I slip up? What if I fail? There is no freedom of movement.

It turns out the key is in the movement. An intention is such a movement. We aim in a direction and we move towards it. But how do we stay on track? Is it sheer will, or is there something else that helps us stay the course?

There is something else! What changes the dance is when the movement is within a bounded space – a space that protects from outside influences and pressures and “shoulds” and even good things that threaten to take away time from the important things. The bounded space becomes a buffer to all that moves in, pushes in or constricts; to the attractive and the uninvited; to the temptations and the easy answers; to all the things that keep us from keeping our loved ones close.

There is something else! What changes the dance is when the movement is within a bounded space – a space that protects from outside influences and pressures and “shoulds” and even good things that threaten to take away time from the important things. The bounded space becomes a buffer to all that moves in, pushes in or constricts; to the attractive and the uninvited; to the temptations and the easy answers; to all the things that keep us from keeping our loved ones close.

If I spend time and energy focused on the “should have’s” and how I couldn’t manage to do it right, I find myself stuck again, going in circles or paralyzed yet again. What I need to do in those times is start asking the kinds of questions that will allow for movement again: What could I do now to make a difference? What obstacles seem to be constantly in my way? What structures and routines do I need to put in place to make it easier to get there?

We have many structures, routines, and rituals in our household that we have developed to protect our family time and preserve the things that are important to us. Sitting down at dinner together is one of those rituals that we have worked hard to put in place – it is not always easy and it doesn’t always work, but the intention is there to carve out the time. Reading to my girls before bed is another ritual that I have greatly enjoyed over the years. This, too, takes work to preserve, as there are so many things that could get in the way. When my girls became teenagers, I started a tradition where I took each one away for a weekend – just the two of us. I carve out space to spend time away from our regular schedules and routines, away from our digital devices. Again, not easy when we are all involved in so many things – but if it’s important to me, if it is what I yearn towards, I will find a way.

One of the most impacting and helpful structures I have put in place in my life is to set aside each week a day of rest – a day without agendas, without “shoulds,” without email, without anything that feels like work… a day for family. This has been one of the hardest things to do and felt like an impossibility for many years. As all things do, it began as an intention. I wanted, and needed, a space in time where the pressures of the world were kept at bay. A bounded space where I had freedom within to move, to rest, to play, to create, to be present with my family. The paradox of the bounded space is that it creates freedom within the structure. It allows me to be present in the now because I have physically and mentally blocked off the time, and my energy is not pulled in different directions. And so the intention was born, and I moved towards it for at least a year, if not more, before it was realized. I was very careful not to make this day a rigid rule that could be broken, but rather an intention to be honoured.

In returning now to my resolutions, what if I were to replace the word resolution with intention? Suddenly that changes everything. My resolutions are replaced with: I intend to spend more time with my children; I intend to exercise more and eat better; I intend to have a clean house. I yearn in those directions. I have something to aim for, and something to move towards. I may not always hit the mark. I may mess up when I get tired, or alarmed, or frustrated. In fact, I can anticipate that there will be times when it will be harder to realize my intentions. I will need to make room for the frustration that comes when I fall short. And I will need to create structures and routines to make it easier to realize my intentions – whether with family, health, or a clean house.

Intentions allow us to come alongside, to make room for the emotion that is stirred up, and to find a way through. We can do this with ourselves, and even more importantly, we can do this with our children. We can draw out their intentions, help them find their steering wheel, and aim in the right direction. We can come alongside when they mess up, make room for the frustration, and honour their intentions. We can look and see where the obstacles are, realizing that some obstacles will need to be faced, while others just need to be moved out of the way. We can create a bounded space for them – a place where they feel loved and where they are free to move, to play, to grow, and where their intentions can be realized… eventually!

Digital devices provide kids with the capacity to connect with each other like never before. No longer confined by geography , classroom walls or home, they have unprecedented access to a constant stream of friends, information and entertainment. While our kids emerge as savvy inhabitants of this digital world, parents are left to monitor, negotiate, and police their child’s online interactions and activities.

Digital devices provide kids with the capacity to connect with each other like never before. No longer confined by geography , classroom walls or home, they have unprecedented access to a constant stream of friends, information and entertainment. While our kids emerge as savvy inhabitants of this digital world, parents are left to monitor, negotiate, and police their child’s online interactions and activities.

While it is clear the digital age presents new challenges to parents in terms of holding onto their kids, what is often missed is how this is colliding with the phenomena of peer orientation. Traditionally, children have oriented around their adults but in the last 50 years many are taking their cues, values and bearings from each other and at the expense of adult influence. There are many reasons contributing to the rise of peer orientation stemming from changes in family structure, economics, and increased geographic mobility. Children have become increasingly separated from the adults who are responsible for them, leaving them with relational voids that are often filled with peers. As if in a perfect storm, our children’s enhanced capacity to use digital devices comes at a time where their drive to be with one another is at an all time high. When our kids prefer to be with their peers they can feel miles away from the adults who care for them. They occupy themselves in connecting to people and places in a digital world that many parents feel they are shut out of.

The answer to keeping our children close lies in cultivating, deep, strong, caring relationships with them. You cannot take care of a child if you do not have their heart. Parents play need to take up the responsibility for the relationship with their kids – but what are some of the ways this is lived out loud?

1) Collect our Children -Collecting a child is an attachment ritual used to activate relational instincts to depend on, look up to, trust, and follow. In collecting a child we seek to get in their face in a friendly way and try and get a smile, a nod, and an overall sense of warmth and connection between us. In pursuing them in this manner we gather them to us and invite them into relationship. The warmth, delight and enjoyment we express conveys we are the one who will take care of them and provide for their relational needs. It is this collecting dance that builds the deep, caring relationships parents need that will help them hold onto their kids.

2) Nurture to Fulfill Attachment Hunger – Parents can best nurture their children when they seize the lead in the attachment dance. Reading their child’s need for contact and closeness and providing generously for them conveys they are holding onto them and are their best bet. The provision of care a parents offer needs to be greater than a child’s pursuit for connection, that is, if they need a hug, we have three in return. When a child feels there is a generous invitation to exist in their parents presence they hold onto them in return, seeing them as the ones to take care and nourish them.

3) Preserve the Connection at all times – There are many things that can come between a parent and child including behaviour, unmet expectations, and strong emotions. While adults need to convey rules and reminders of appropriate conduct when infractions have occurred, they must also communicate through words and deed that the relationship is still intact. If behaviour or conduct has come between us, we must find a way to hang onto a child and impressing upon them that our desire to take care of them remains unwavering. To send them out into the world hungry for connection due to perceived breaks in our relationship pushes our children into connection with each other and out of orbit with us. Parents must assume their rightful position as being responsible for the parent-child relationship, especially when faced with conduct that is less than ideal.

4) Protect Against Competing Activities and Attachments – Keeping children close in a digital world requires the conscious creation of structure and rules around the use of communication devices and peer interaction. Why would we allow children to use their devices at the dinner table where we were meant to collect their eyes and listen to their stories? Why would we allow them to retreat to their room with their devices seeking connection with others and eroding their appetite for interaction with us? We must consciously create rules and structure around the use of digital devices and peer engagement that will preserve and protect our relationship with them. As we set rules and rituals around technology use, parents must lead by example. We cannot let our love for our new tools blind us to the responsibility we have in creating a context for their safe use in and out of the home.

5) Matchmake to Build a Village – We cannot leave it in our children’s hands to build the village that will raise them. Parents need to take an active role in introducing and match making their children to adults who are responsible for them. Coaches, teachers or extended family members are potential attachment figures that can provide for a child’s needs rather than leaving them to their own devices and often in the hands of their peers. By matchmaking we set our children up to fall into attachment with other adults, drawing attention to similarities between them and the warmth that is there.

Social media and the enhanced capacity to keep one’s peers close was born from relational hunger and fuels it today. The best inoculation against losing our children to their peers and the online world are deep nourishing relationship where parents present themselves as the answer to their child’s needs. If we hold onto our children they are more likely to hold onto us and see us as their best bet. May we remain conscious enough of the challenges that lay before us so we can steer our children into the digital age while at the same time holding onto our relationships with them.

Ralfe Clench was a kind of genius, and a memorable character, whose job was in the administration department at Queenʼs University: he determined the course schedule, by hand, for 2,000 students in the days before computers, and he knew the human face that went with each schedule. He was also the self-appointed (and unofficial) teacher who brought those of us who had not taken Grade 13 calculus in line with our mathematics requirement during first year. He knew what we needed and offered it to us just because he cared.

Ralfe was a tall, plump man with a moon face under a bowl haircut and a Charlie Chaplin mustache who wore the same clothes (or their duplicates) every day, as well as a huge leather utility belt cinched around where his waist used to be. He strode around campus at high speed, and arrived for every class precisely on the last stroke of the starting bell, while declaring the opening statement of the lesson as he entered the room. He lectured until precisely the first stroke of the bell indicating the end of class, at which point he whisked out of the classroom, trench coat flapping behind him, utility belt clanking. He was an unforgettable eccentric, known to all on campus.

These days, Ralfe would probably qualify for various psychiatric diagnoses. He was rigid about his routine, his clothes, his entire life. He was strict about our classroom conduct, including where we sat (he memorized our names on day one, and that was to be our spot for the rest of the year). He was weird too: he lived in a house where all his belongings were filed in grey office file cabinets and his long-suffering wife lived on a different floor; he subsisted on cola drinks and chocolate bars. He was a modest man who did not seek recognition, but most of the rumours that sprang up about him were true. He might have been a nightmare, but he was a kind, whimsical figure, a legend in his time, like a character from a Stephen Leacock story come to life.

We adored him. We learned calculus from him. Instead of feeling coerced into youthful counterwill, we toed the precise lines he drew. Homework was to be handed in each week in correct order, in one format only, folded precisely thus, as part of the “time and motion study” kind of life he lived. He explained that the rituals saved his marking assistant measured minutes per week and ensured we got our correct mark. This assistant came into class at the same time twice a week to collect or distribute homework assignments.

We adored him. We learned calculus from him. Instead of feeling coerced into youthful counterwill, we toed the precise lines he drew. Homework was to be handed in each week in correct order, in one format only, folded precisely thus, as part of the “time and motion study” kind of life he lived. He explained that the rituals saved his marking assistant measured minutes per week and ensured we got our correct mark. This assistant came into class at the same time twice a week to collect or distribute homework assignments.

Ralfe was a master teacher. He was able to write calculus examples across the blackboards at the same time as speaking sentences of the theory, a talent I have never seen in anyone else. He sometimes mentioned that he was in a curious position because he was not a university professor. We had no doubt he taught because he adored the subject. He was witty and kind, dramatic and gentle with us, and we felt safe with him. He would call a loud and surprising “hello!” from across the street if he saw one of us outside class, and in the overwhelming days of the bewildering first year, he helped me feel known and appreciated. He even knew what city I had come from, the name of my high school, and my Grade 12 marks.

Oh yes, the utility belt! It was loaded up to contain every tool and item he could possibly need in his daily routine, from pencils to electric drill, chocolate bars to walkie-talkie. One day we locked him out of the room just to see what would happen. We heard him arrive as the last strokes of the class bell chimed. Then a series of clinks and clanks mingled with his usual jolly declaiming of the opening remarks of his lecture. We deduced that he was finding in his belt a variety of tools, which he briskly used to remove the door via the hinges. The door came away, and he laid it against the wall of the corridor, now well into the day’s lecture. Then he walked into the room without pause, said not one word about our trick, presented his entire class without a hitch, and on the stroke of the bell walked out as usual, stopping however to put the door back on its hinges, still locked on the inside. The class erupted. He had not skipped a single beat and never referred to the incident, yet he had an especially brilliant twinkle in his eye for the rest of the day.

While personal subjects and emotions were not in his vocabulary, he knew he was loved by all his flock of students over the years. Many shared personal stories about him in the university journals. His obituary a couple of years ago brought tears to my eyes.

When I was 18, setting off enthusiastically to a university in another province for my first experience of living away from home, I had no idea that what I needed most was a nurturing relationship with my calculus teacher. I never had a real conversation with him and I never sought him out for advice, though heaven knows I needed some, but the warm glimmer in his eye and his shouted “heigh-ho, Liz,” anchored me and kept me safe for a whole school year. It is only now, looking back, that I recognize the truth that the invitation to exist in one adult’s eyes at just the right moment is the very breath of life that gives our puny adolescent wings liftoff. I even got a decent mark in calculus.

Guest Contributor Liz Hatherell is a certified Neufeld Course Facilitator who lives in Winnipeg.

When Gail posted her item about a favourite or memorable teacher, I cast my mind back to my school days. I had a couple of teachers who I know liked me but none stood out as particularly special. I didn’t meet my significant mentor until I was well into my own career as a teacher. I was the third of five children in my family, and at school I followed my brilliant oldest sister and my incredibly artistic next oldest sister so I always felt that I did not measure up academically or creatively. In those days, teachers still compared siblings and, more than I would ever like to remember, I was asked why I could not be more like my siblings. I think I was a happy-go-lucky kid who was pretty relaxed and not overly motivated to do more than whatever would keep my parents from being too upset with me. I participated in lots of co-curricular activities but was never the debater my sister was, nor the athlete my other sister was.

When Gail posted her item about a favourite or memorable teacher, I cast my mind back to my school days. I had a couple of teachers who I know liked me but none stood out as particularly special. I didn’t meet my significant mentor until I was well into my own career as a teacher. I was the third of five children in my family, and at school I followed my brilliant oldest sister and my incredibly artistic next oldest sister so I always felt that I did not measure up academically or creatively. In those days, teachers still compared siblings and, more than I would ever like to remember, I was asked why I could not be more like my siblings. I think I was a happy-go-lucky kid who was pretty relaxed and not overly motivated to do more than whatever would keep my parents from being too upset with me. I participated in lots of co-curricular activities but was never the debater my sister was, nor the athlete my other sister was.

When it came time to go to university, I had no idea what I wanted to do and found myself working on a B.Ed. with others who had wanted to be teachers their whole lives. I liked the idea of teaching but was not in love with it. Finally, though, I found myself in front of a class of Grade 4s, mostly First Nations kids, and I started to love what I was doing. I was very young and still had a lot to learn.

I remember in my first year of teaching, a Grade 7 boy told me to “f%#k off”, and I was outraged. In high dudgeon, I went to the principal and told him what this boy had done and asked what was he going to do about it? He was very calm and gentle and asked me kindly what had I done to allow the situation to escalate to that point? I was stunned. I had expected that he would haul the child into the office and at least send him home for the day. Instead, the principal asked me to look at how I might have handled things differently. On reflection, I realized that I had pushed the child into a corner and there was no way for him to save face, never mind have any sort of positive relationship with me. That moment of recognition was pivotal and helped me begin to put myself in the shoes of the children I taught.

Flash forward 17 years and I began work in Victoria, hired to open the first Learning Support department this high school had ever had. I loved this position because I worked exclusively on a one-on-one basis with struggling students. I was their teacher and advocate, and found myself, more than ever before, in close relationships with parents who were worried sick about children who found school extremely challenging. Over the next few years I was encouraged to apply for leadership positions in the school, eventually being appointed as the Director of Student Life; in other words, the school disciplinarian.

Two things happened to me at about that time. First, I came across Gordon Neufeld and his material on attachment, which gave me permission to follow my buried instincts to work from within relationships. Second, the school hired a new principal in our Middle School, David Graham. I had to work closely with him as his vice -principal. He had never heard of the developmental paradigm nor Dr. Neufeld, but he lived and breathed it every day, nurturing relationships from the moment he set foot on our campus. He wooed teachers, parents, and most of all his students. He quickly got to know every student in the school and found ways to connect with each of them as often as possible. He was always around with his camera and took hundreds of pictures to send home to let parents know he was noticing their children. He made a point of connecting with every teacher at least once a day, popping into classrooms and saying hi. He was in the car park before school and at the end of the day greeting parents and children as they arrived at school and saying goodbye as they left in the afternoon. He was at every sports game, play practice, and after-school help session. He was unfailingly positive; his smile was genuine and everyone he came across basked in the warmth of his presence. He made me feel as though I was capable and very good at my job. He understood me and through his mentorship always made me want to be my better self. David gave me the courage to think about further leadership opportunities; he made me feel as though I could do anything I set my mind to.

I learned a lot! I learned to ALWAYS look at any problem at school by figuring out what would be best for the child and to make all decisions based on that perspective. I learned that the adults in an organization need to feel the relationship as well. It became clear to me that when people feel valued and appreciated, they want to do their best and work with their leaders as a team, creating a school full of warmth and support. I learned that I need to tell my colleagues that I care and think highly of them and the work they do. It is hard to describe how much I learned but the mentoring from this amazing man, combined with all the things I was learning from Gordon Neufeld, allowed me to relax and follow my intuitions, and I found I enjoyed my work more and more every day.

Sadly, in his third year at our school, David Graham became very ill and had to go on long-term sick leave. I became the acting principal for the next two years as his health failed and David finally passed away. While I was covering for him, he and I would chat often and I would ask his advice on some of the more complicated problems as they arose. He always pointed me in the right direction by telling me that I already knew what to do and must follow my instincts.

I am now in my dream job as principal of our Junior School and I attribute my appointment to what I have learned from Gordon Neufeld and David Graham. These two people came into my life when I was most able to hear and understand what they were teaching. Every day at work, I try to emulate and honour what David taught me. Though he has been gone for three years now, I think of him very often and when I face a particularly difficult issue, I ask myself “What would David do?” and the best answer comes! I am old enough to be the parent of most of our school parents and I notice that they often come to me for parenting support as well as help with navigating the education of their children. I work very hard to develop relationships with everyone in our school community. I know all the children, their parents, and of course the teachers. I spend most of my days at school working on these relationships, which are the most enjoyable part of my job. I feel incredibly lucky to have ended up here and I am grateful to these mentors every single day!

Jean Bigelow is a Junior School principal and parent consultant. She has extensive experience working with students of all ages—most recently elementary school students. Jean is also a parent and grandparent who puts Dr. Neufeld’s approach to use in her daily life.

What would our world be like if our children’s teachers provided warm, secure, and loving relationships with our children before implementing any learning programs? What if our children could look forward to going to school each day with enthusiasm, eager to see their caring teachers?

What would our world be like if our children’s teachers provided warm, secure, and loving relationships with our children before implementing any learning programs? What if our children could look forward to going to school each day with enthusiasm, eager to see their caring teachers?

When I look back through my own school years, I can’t remember being attached to any teacher until I met Miss Perkins in the 7th Grade. Miss Perkins was not a young bachelorette, but rather a grandmotherly woman who never married. She showered delight and love on our class of 15 girls as if we were her own children. I realize only now that my love for literature and poetry blossomed as a result of sitting in the front row of her classroom throughout junior high and high school.

In those days my school had a policy to give blue slips and red slips to students. The blue slips were for good behaviour and scholastic achievement. The red slips….well, they were for the opposite. Of course, I only got blue slips from Miss Perkins, until the day came when I had to take home a red slip. We were learning “The Song of Hiawatha,” and when we came to the line “By the shores of Gitche Gumee” I had a fit of uncontrollable laughter. If that weren’t bad enough, the principal just then walked into our classroom and I turned into a pile of hysterical giggles. I loved Miss Perkins so much that I was not the least bit perturbed to have to write a composition as a “punishment” to accompany my red slip. After Miss Perkins read my work, she responded with utter delight to the ideas I expressed and gave me an A. From Miss Perkins, even a red slip didn’t feel like a punishment but instead another opportunity to experience her enjoyment of us. Her frequent smiles were filled with warmth, and I’m sure every girl in the class felt that she was Miss Perkins’ favourite student.

Although we had an hour of free time for lunch, in 11th Grade we chose to spend this time with Miss Perkins. We would rush to her classroom so as not to miss anything. I never cared much for the works of William Shakespeare, but reading Macbeth over sandwiches and chocolate milk was one of the highlights of my school day. Thanks to Miss Perkins, Shakespeare’s plays inspired many different discussions and much of my own writing.

That was, my goodness, about 45 years ago. Yet as I recall how Miss Perkins enjoyed having us in her classroom, I can still hear her jolly laughter.

After I graduated from high school, I met another teacher who had a profound impact on me. I had just turned 18 and had moved over 3,000 km away from home to go to college, just a couple of years after my parents divorced.

I had never heard of “sociology” before but ended up in Prof. Greenberg’s class by chance. He was tallish and thin, and had a crisp, friendly voice, welcoming us into his classroom with enthusiasm. He always wore a blue plaid jacket, and had a short, greying beard which I later learned was actually a long beard rolled and neatly tied with a rubber band under his chin so no one could see it.

I wasn’t sure why at the time, but I fell in love with sociology. Since Prof. Greenberg was almost the only teacher on faculty who taught it, I registered for every single one of his courses. By the end of my sophomore year, I had completed all my requirements for a BA in – you guessed it – sociology. I originally thought I wanted to be a social worker so I could take care of people, but after Prof. Greenberg explained how the two fields completely clashed, I followed him. (Besides, there were no social work courses in the college.) Perhaps due to Prof. Greenberg’s influence, my college had more students majoring in sociology than in any other area of study.

Prof. Greenberg’s classes were full. He loved the material. He taught with great delight, exuberance, and humour. He invited and loved our questions, and drew us into discussions about the meaning of life. We all came to class on time so we wouldn’t be left out of the action. His door was always open. I remember sitting in his little office with my list of adolescent existential questions; he spent a great deal of time answering each one patiently, honouring my place on my path of growing up and searching for answers to existence.

One day he took out pictures of his 11 children, lined them up on his desk, and playfully encouraged us to test him on their names and ages. He invited some of us – I guess those who were hungry for family – to his home for the Sabbath, to join the many students who sat around the table together with his family to enjoy singing, learning, and discussion. Sabbath was also the time when he wore his beard long and replaced the plaid jacket with traditional Sabbath clothing.

He cared about us, as well as our ideas and opinions, and he helped us to analyze one another’s thoughts and theories with similar appreciation and respect. His tests were always essay tests because the more we expressed ourselves, the better.

He was a great teacher not because of anything in particular he did, but because of who he was. We wanted to follow him, and he made learning seem like the greatest adventure in the world. He seemed to embrace life with a pure and knowing heart, and there was something magical about that.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if our children had teachers like Miss Perkins and Prof. Greenberg throughout their years in school?

I started Kindergarten two months after turning five, and eight months after my father died. My teacher was Miss Neronovich. She smelled wonderful. She was young and pretty with a tall golden beehive hair-do, short bright-coloured skirts, and the most inviting smile and warm eyes I could imagine. I fell in love with her on the first day we met, which was a special date when my Mother and I went together to her classroom so that she could meet me and show me around. My Mummy was just starting to eat again, and no longer stayed in her housecoat all the time on the weekends, and I remember clearly before our special meeting that she coached me on how to say “Miss Ner On A Vich,” and told me what a nice lady she was, and how I was lucky because I was going to a special class that was going to be a school family. It was 1973, and our local school was trying out a new-fangled style of classroom called “family grouping.” My mom said Miss Neronovich especially wanted to meet me.

I started Kindergarten two months after turning five, and eight months after my father died. My teacher was Miss Neronovich. She smelled wonderful. She was young and pretty with a tall golden beehive hair-do, short bright-coloured skirts, and the most inviting smile and warm eyes I could imagine. I fell in love with her on the first day we met, which was a special date when my Mother and I went together to her classroom so that she could meet me and show me around. My Mummy was just starting to eat again, and no longer stayed in her housecoat all the time on the weekends, and I remember clearly before our special meeting that she coached me on how to say “Miss Ner On A Vich,” and told me what a nice lady she was, and how I was lucky because I was going to a special class that was going to be a school family. It was 1973, and our local school was trying out a new-fangled style of classroom called “family grouping.” My mom said Miss Neronovich especially wanted to meet me.

The class consisted of children from Kindergarten to Grade 3; we sat at tables together, and we little ones were invited to ask the big ones for help if we needed it. We got to choose our own work, moved around the classroom freely from one “centre” to another, and when we needed help or had completed any work, we took it to Miss Neronovich to tell her about it, and she would look at it with us one-on-one, and make a comment, or show us something we didn’t know, or help us with something hard. When I close my eyes I can still remember leaning on her knee with my little notebook in her lap, her arm around me, and our yellow heads close together while I dictated a story, and she printed it neatly for me under my crayoned illustration.

The only difficult time on my first day was a cruel invention called “recess.” I clearly remember my sense of panic when we were ushered outside without Miss. Neronovich. Thank goodness I was only alone for a few moments, though, as Mr. Greyall came to my rescue. He was the Principal, and he walked the playground at recess. On my first day of school he saw me and held out his hand to me so that I could walk with him. I don’t remember talking to him, or what he said to me, but I do remember the feel of his big warm hand around mine as we walked. I don’t remember ever being told to go play with the other children, or to leave him alone, or that he was too busy, or that someone else needed him. My memory is that I walked with him every day, and that I was safe. Kindergarten was a dream – a beautiful dream.

Grade 1 was the same – because of “family grouping,” I got to stay with my Miss. Neronovich, only now I stayed all day, and so I got to walk with Mr. Greyall at lunchtime too. I also got to help the little Kindergarten kids who were a bit scared and didn’t always know what to do, and as the year went on I even started playing on the playground sometimes, as the big children taught me to play hopscotch, and to skip, and to play cats cradle. I remember that Irene, one of the big Grade 3 girls stopped a little boy from calling me “Baby ears.” She told me if he did it again I could come and tell her, and she would get a grown-up for me.

At the assembly at the end of the year, Mr. Greyall announced his retirement and gave a long speech about all the things he would miss about Norquay elementary school. One of the things was “walking every day with little Pammy.” I knew I mattered to him, and that he would remember me.

My report cards for Kindergarten and Grade 1 were glowing. I was smart and good, and a delight to have in the classroom.

In Grade 2 we moved to a “better neighbourhood,” from East Vancouver to Kerrisdale. My new school was a “better school.” My mom was so happy to be moving her little family (my sister and me) up and away from a time of great sorrow, and so glad to be able to offer us “better” than the little pink house on E. 29th St.

My new school was a traditional school, not given to flights of fancy such as “family grouping.” No-one there seemed to understand that I came from a school with a somewhat unconventional approach, and that I didn’t know the rules for a “normal” classroom. Certainly I was not in any way oriented to the change of expectations. I didn’t know that we children were not allowed to talk to each other; I didn’t know it was cheating if I asked a classmate for help with a question; I didn’t know I was supposed to raise my hand and ask before getting up to get a tissue; I didn’t know that I couldn’t walk freely to the window to look at the robin on the grass, or freely to the teacher with my work to ask for feedback or help. I didn’t know.

I also didn’t know anything about math. In our “family grouping” system, the idea was that children had until Grade 3 to accomplish a particular set of competencies. We had to do a minimum of two activities from each centre every day, but once those were completed we could do as many extras as we wished, from whichever centre most interested us. I was interested in reading and writing and music, and I loved the dress-up centre, and the big blocks, so I chose to spend much of my time in these pursuits. I had completed many grades worth of reading and writing modules, but was still at the manipulatives stage with math. I knew my numbers, perhaps to 20; could do all kinds of geometry puzzle games; could sort beads by their attributes and string them into patterns; I could arrange Cuisenaire rods from shortest to longest, but I could not manage much more than that. Nobody had been concerned about this at all, as it was felt that I still had two years to “catch up”. I had no clue that such a thing as “behind” existed.

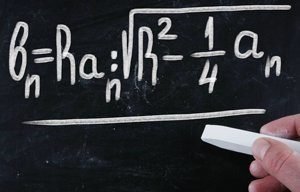

My Grade 2 “teacher” (who shall remain un-named), had only one agenda on the first day of class, as far as I could see: she wanted to trick me. She stood at the front of the room and talked at us while she wrote on the board. I could read, and what she was putting on the board didn’t make any sense at all: it was some kind of trick. She wrote a series of numbers something like this:

4+6=

3+2=

1+1=

8+5=

and then asked us what the answers were. I got the numbers, but what were those other weird shapes? I knew it was some kind of code – that the numbers were meant to relate to each other in some way, but I couldn’t find the pattern. I realized within minutes that the other kids seemed to know the code. I remember the white panic as I realized that I didn’t know what to do, and that I wasn’t allowed to ask for help – it was as if my ears started buzzing and my eyes lost their ability to make sense of what they were seeing. When called upon, I made random guesses, calling out whatever number first came to mind, but I didn’t know anything. It only took me a couple of hours to realize how stupid I was, and only a couple of days to realize what a bad child I was. Because I was so bad and stupid, my teacher didn’t like me. I was always in trouble for not following the rules – I tried to anticipate them, but who knew that reading a library book or sharpening one’s pencil so that work could be done, required permission?

I hated being in that classroom. I was in a special reading group (I thought it was because I was dumb and bad, but looking back, I realize that it was a pullout program for advanced readers), and we got to escape to a special classroom two or three times per week. To get there we walked through the library. As we were walking back to the classroom one day, I felt more and more sick about being with my “teacher” again. I was at the back of the line, and as we passed through the library I found myself ducking behind a bookshelf while everyone else kept walking. My heart was beating, but there before my eyes was an interesting looking book. It was a book about children who found a secret world. I stayed in the library and read it until lunchtime, and nobody noticed, and I didn’t have to be with my mean teacher. I knew it was wrong, and I wasn’t allowed, but I couldn’t help myself. I managed to do the same thing again a few days later, this time on purpose. Unfortunately, though, someone came and found me, and I got in trouble for being sneaky and skipping out of class.

On the playground there was nobody to take care of me, and all the other little girls were friends from the two years before. There was another new girl, though, called “Julie.” She talked funny because she was from Australia, and she was bad. She got in trouble all the time, and even had been sent to the principal’s office. She invited me to be her friend, and I said yes, but I was trying to be friends with the good girls too. At lunch they said I had to choose between Julie and them, but Julie was already my friend, so I had to choose her or I would be mean.

One day Julie said, “let’s dance on the grass!” There was a grassy place at the front of the school where we weren’t allowed to go – it was just grass for decoration, not for playing. I knew that, and I said that we weren’t allowed, but Julie said if I was her real friend I would go with her, and I wanted to be a good friend, so I did. Then we danced, and actually it was really fun, and when Julie held her skirt way up as she danced, I joined her. We got sent to the principal’s office. My mom was engaged to be married at the time, and the wedding was coming up in just a few months. The principal told me that I would disappoint my mother and ruin her happiness at her wedding if she knew what I did, and so she wouldn’t tell her this time, but I had better not do anything bad again or she would tell. So I had to keep the painful secret from my mother.

My Grade 2 report card was less than glowing.

That summer my mom got married, and we moved to a fancy big house and I switched to a new school again. It was Grade 3 and I met Mrs. Tiller. She was VERY strict and no nonsense. And she loved me. She loved me right away. I could tell from the twinkle in her eyes when she met me at the door and welcomed me to her class. On the first week she handed out a mimeographed math test. I had finally figured out minus and plus by the end of Grade 2, but I had never seen a division sign. The kids at the new school started division in Grade 2, but we hadn’t started it yet in my old school. So when I was given a sheet of division problems, I thought all the little dots were some kind of malfunction of the mimeograph machine, and answered the questions as if they were subtraction questions.

Later that day Mrs. Tiller came over to my desk and leaned over to talk to me quietly so nobody could hear. She said “I think you haven’t done division yet, but don’t worry, I’ll show it to you. It’s easy, and you’ll figure it out in no time.” So I knew for sure that she would help me and that I was safe. Mrs. Tiller invited me to read when I was done my work, and suggested new books she thought I might like. Once when my cat followed me to school I was afraid to go into the class, because I thought my cat would be lost and get hit by a car. A classmate alerted Mrs. Tiller to my problem, and she came outside, picked up my cat, took her inside with us, and announced to the class that we had a very special visitor for the morning. Then at lunch she carried my cat all the way back home for me. I was lucky to be in Mrs. Tiller’s class for Grade 3, and got to stay in the same school and have her again in Grade 4 even though my mom’s new marriage had not gone well – there was a divorce and we moved into a townhouse.

My report cards show that I was both smart and good again in Grades 3 and 4.

In the summer before Grade 5 we moved to Richmond, so I switched schools again, but I’ll end my story here saying that at the end of Grade 4, knowing that I was moving, Mrs. Tiller gave me her home phone number and said she would love to hear how I was from time to time. My mom bought me my own little phone book just so I could keep my teacher’s number somewhere that was especially mine. I did call, at first every few months, then every year or two, and then just to share big events like my marriage and the births of my children.

I was dumb and bad; I was smart and good. My teachers showed me so.

The other day I had a bit of a shock when I realized Mrs. Haskins, my beloved grade 2 and 3 teacher, would now be close to 100 years old. Mrs. Haskins was one of my favourite teachers because she had a wonderful blend of alpha qualities; she was kind yet firm. She was definitely in charge but in such a compassionate way that we could rest, secure in the knowledge that she would look after all of us.

The other day I had a bit of a shock when I realized Mrs. Haskins, my beloved grade 2 and 3 teacher, would now be close to 100 years old. Mrs. Haskins was one of my favourite teachers because she had a wonderful blend of alpha qualities; she was kind yet firm. She was definitely in charge but in such a compassionate way that we could rest, secure in the knowledge that she would look after all of us.

I remember her as being kind to everyone. She was even kind to awful Kevin R. who occasionally peed under the steps. She was kind to Darren P. who smelled and sometimes swore.

One day when we had a substitute teacher, Richard M. wrote a nasty note about how he was going to murder the woman. She was distressed by the written attack and so she shamed him in front of the class. With disgust on her face and harsh scorn in her tone, she tried to pull a moral conscience out of him right there and then. As she demanded he apologize to her in front of the class, we all sat horrified, as this was not common practice in our classroom. When she couldn’t extract an apology from him, she sent him to the Silly Chair (a place in the office reserved for wayward students). When Mrs. Haskins returned from her absence, I overheard as she took Richard aside and simply said, “Richard, it’s hard when I’m away isn’t it? I missed you and I’m glad to be back.” She never mentioned the violent note he had written to the substitute. He settled back down to his usual self. She understood that Richard didn’t function very well when she was away. Although at eight years old I had my judgments about Richard, knowing that Mrs. Haskins would protect even kids who got in trouble made me feel safe in her care.

When it was her duty day at recess, she had a huge following of primary students who wanted to be with her. Every few minutes, she jogged a little before returning to her normal stroll. This game drew big crowds, and also gave us the impression that she enjoyed our company and shared our sense of fun. While the other teachers just wandered around watching us from afar, she created a predictable game that we loved and invited us to join her circle.

Mrs. Haskins didn’t come across as some stony teacher-figure who lived at school, but revealed herself as a real human being. She brought artifacts from the Queen Charlotte Islands into our class, and showed us photographs of herself, leading an adventurous life there. She treated us as though we were her children. She delighted in us.

I had a sneaking but very strong suspicion that I was her favourite. But years later, when I shared my belief with a friend, she laughed saying, “I always thought I was her favourite!” I think Mrs. Haskins made everyone feel this way. For her, each of us was significant and all were worthy of special consideration. She invited us to exist in her presence.

She never once raised her voice or humiliated us (I was very sensitive to this as a child). But she could be firm too. When Ian R. kissed me by the locker and I didn’t want to sit by him anymore, she took me aside and told me she was confident that I would be okay. She said she wasn’t going to move me but she’d make sure I was fine. I trusted her and found my courage. She could be the agent of futility but always the angel of comfort at the same time.

I doubt Mrs. Haskins is alive today. I’m sad to think she is no longer on this earth. As I write about her, I realize that she is still with me in my heart – attachments are forever – and I see that she played a huge part in my career choice as an educator. The feeling she gave me when I was with her is exactly what I aspire to offer my own students. She collected and protected us; she loved learning, and because we loved her, we loved learning too. She respected our dignity, treated us fairly, and always, always conveyed to us, “I am exactly where I want to be – teaching you!”

I still remember my parents’ conversation. I was playing on the living room floor. My ears pricked up when I heard my father saying to my mother, “Well, we want her to have a good Grade One teacher to give her a good start, and Miss Cox is the better of the two teachers.”

Yay! School! Yay! Reading! I don’t remember much about Miss Cox, nor do I recall her paying any attention to me, but I had things I wanted to learn. Especially I wanted to read! My father explained to me much later that I had expressed a very early interest in reading, but my parents didn’t teach me the alphabet lest I be bored in school.

I discovered that school had strange rules, including having to sit still at a desk for a long time (this was definitely boring) and being punctual. I was shocked that kids were mean to each other and that recess was a terrible anarchy. Nonetheless, I was immensely pleased with myself when I could make sense of the marks on the page and could take my Dick and Jane books home to read out loud to the family!

Grade One was a gentle introduction; the hurly-burly got much worse as I moved through the grades. I still remember the misery of a year with Mrs. Handby, an old-style British Empire tyrant. She terrorized us all with shouting and shaming, sharp raps from her pointer, and lurid images of hell-fire. She had deadly aim with her chalk ‘bullets’ and eyes in the back of her head.

I was scared of Mrs. Handby and kept out of her line of fire as much as possible, but I did manage to learn what was on offer in spite of her dreadful style. My teachers didn’t have a lasting impact on me because I went to school for my dad. He seemed to think learning things was important, and was always interested in what I was being taught and how I responded. He supported my own interest and curiosity because he delighted in my learning. (This is profoundly different from rewarding me for good grades, which he never did). I was shielded by this all-powerful attachment from my worst experiences; my relationship with my dad protected me from the trauma a teacher like Mrs. Handby might have inflicted. I felt he was for me always and that he knew everything!

I can remember another teacher in a later grade telling us in a math lesson about calculating the circumference of a circle – you had to multiply the diameter by pi. I asked, “What IS this pie?” The response was, “Don’t ask, just do it,” to which I replied, “I’m going to ask my Father!” That evening after supper, he supplied me with the explanation I needed: “It’s a Greek letter that symbolizes the ratio of the circumference to the diameter.”

My birthday was in November, and my parents considered me a ‘worry wart,’ so they delayed my introduction to school, my first experience outside the protective shelter of my family, until I was almost seven. By this time I had gone through what the pioneer Swiss cognitive researcher Jean Piaget calls “the 5-7 shift.” This shift marks a big enhancement in brain function, as children become able to consider two things in relationship to one another, rather than one at a time. Along with this shift comes the ability to see differences, to take things into context, and to feel two competing impulses simultaneously. My newfound ability to understand symbols (e.g. this mark on the paper stands for a sound, or a number) gave me an advantage over less mature classmates. Contextual thinking also makes it possible to anticipate consequences and thus avoid getting into trouble. Seeing and understanding difference, in addition to enabling me to hold on to my inner image of my father, made me less affected by peer pressures.

In my father, I had a teacher who didn’t change every grade, who was there every night in his big chair, often expounding his latest theories. I cared about what he thought of me much more than I did about what others thought.

My relationship with my father carried me through until I started university, when a real chasm opened between us. After all those years of his invitation to me to show my own interests, I was ready to declare that my choice of vocation was mine, and not an extension of his wishes for me. Earlier in my life there was no difference in our intentions but I now found there was no room in that relationship for me to discover my calling. I was very unsure of what I wanted to do. It wasn’t that I had a clear career path in mind and we were at odds, it was the uncertainty I felt that caused me to resist any direction from him.

The years of adolescence and early adulthood are a natural time for young people to seek their own paths, and other adult attachments are so useful when those at home are not giving enough room for emerging interests to unfold. As I grew beyond my father’s plans for my future, I began to feel that now there was no one who cared whether I went to a good school, had a good education, or had enough money to survive!

Missing this adult support and understanding, I felt insecure and easily wounded by criticism. I felt it keenly when my fellow students didn’t like me, and my academic performance was poor.

In my third year of study, I decided to take a course in lithography (I can’t even remember why). The teacher was an eccentric-looking fellow with a wild scraggly beard, fringed and beaded jacket, prominent eyes and a large forehead, and a strange evasive teaching style, as though he wasn’t comfortable with the role of university professor. Once the class was assembled on the first day, he stared at the ceiling and declared, as though to the light fixtures, that lithography was a difficult subject.

I have been thinking for some time about how to describe him. What quality did he have that caused a door to open in me that had been closed until this encounter? Recently he was the subject of a radio program about his artistic career and influence, and I was keen to hear if anyone could identify what made him so very special. The radio documentary portrayed the contrariness and humour of his art, and his technical mastery of a difficult medium, but what was it about him that made him a magnet for young artists and a catalyst for their development? For one thing, he was quite shy in his approach and not in anyone’s face, and he expressed interest and curiosity in a sly, very playful way. I was intrigued by the way he would ask provocative questions to pique our attention. It felt genuine! He really did want to know us! It was as though he was looking to see if ‘anybody was home,’ alert to each student’s potential for self-expression. I could identify with his very personal way of making art – what a new idea– that what was inside you could become the substance of your work!

I had tentative opinions and ideas but had formed a protective habit of keeping them to myself. I wanted to avoid the inevitable “you are weird” response of my peers. I didn’t even realize how much of a secret self I had developed until this professor called me forth! Certainly I knew I had found my better as a ‘weirdo’ – I had never met anyone so fascinating! Many profs were ‘dangerous.’ They could be capriciously and often personally cruel. He seemed completely without that malicious edge.

This was a wonderful time for me. My teacher worked on his own odd and idiosyncratic work in the school studio and welcomed his students to hang out and talk to him. The fussy chemistry of lithography, the strenuousness of the printing process, and the need for access to the press, gave us reasons to spend time with him, working side by side for long hours. The thrill of pulling that first print off the press in his class was equal to my “Dick and Jane” reading excitement in Grade One.

As my father had once done, he provided me with a sheltering attachment. As a result of having one safe place, I found my feet and the rest of my time in school was rich and productive. I always had a person to go to when I was struggling, and I was back to being protected by a relationship that proved remarkably unconditional. He held on to his students long after we graduated and he remains a significant figure in my life.

The benefit of relationships with teachers, mentors, and wise people lasts a lifetime! Whether talking about parents (like my father) or others who provide us with room to be ourselves (like my art prof), Gordon Neufeld identifies an “invitation to exist” as vital to our development.

Separation is provocative for young children because it is connected to their greatest need – attachment. The more immature one is, the greater the longing for contact and closeness because of dependency needs. They desperately need their relationships to work for them because this ensures they will be taken care of. Separation means facing the absence of their attachments and the more dependent they are on them, the more anxiety they potentially experience as a result. It is their desire for contact and closeness that makes them miss us when we are gone. Attachment is the doorway through which separation anxiety opens up.

Separation is provocative for young children because it is connected to their greatest need – attachment. The more immature one is, the greater the longing for contact and closeness because of dependency needs. They desperately need their relationships to work for them because this ensures they will be taken care of. Separation means facing the absence of their attachments and the more dependent they are on them, the more anxiety they potentially experience as a result. It is their desire for contact and closeness that makes them miss us when we are gone. Attachment is the doorway through which separation anxiety opens up.