Editorials by Dr. Gordon Neufeld and the faculty

Our editorials offer insights from Dr. Gordon Neufeld, Dr. Deborah MacNamara, Tamara Strijack, and faculty, applying attachment-based developmental science to the pressing issues of our time. These writings help parents, educators, and professionals navigate complex topics with clarity, wisdom, and a deep understanding of human development.

Looking for a specific topic?

Upcoming Scheduled Classes

Some of our courses are also offered as scheduled classes from time to time with our Faculty providing weekly live special support sessions. If you already have taken the course in its self-paced version, you can enrol in the scheduled class for a fee of only 50 CAD.

Classes Start: March 31, 2026

Tuesdays 10:00AM – 11:00AM PT

Runs for 8 weeks

With Heather Ferguson and Celena Krahn

$250 CAD

Part II of the Power to Parent gets to the heart of developmental science — that growth happens quite spontaneously if conditions are conducive. Neufeld expands on just what those conditions are and the role of parents in the maturing processes. Since growing older is no guarantee of growing up, knowing what children truly need from their parents is key to raising children.

Classes Start: April 2, 2026

Thursdays 10:00 – 11:30AM PT

Runs for 8 weeks

With Tamara Strijack and Jodi Bergman

$250 CAD

Neufeld puts the puzzle pieces together to reveal true play as Nature's way of taking care of emotion. This realization makes sense of the trouble we are now in, as the culture that was meant to take care of play has largely been lost. These insights are distinct to this approach and key to supporting healthy development and emotional well-being in our children and ourselves.

Classes Start: April 8, 2026

Wednesdays: 1:00 – 2:00 PM PT

Runs for 4 weeks

With Lisa Weiner and Robin Brooks-Sherriff

$150 CAD

Today's adolescents live in a hypersexualized culture. Despite their greater exposure and education, current evidence suggests that many youth are in trouble sexually and that their sexual development is not unfolding as it should.

Classes Start: April 14, 2026

Tuesdays 5:30 – 6:30PM PT

Runs for 6 weeks

No one is more susceptible to being misunderstood than the preschooler — especially when adults are trying to rush them out of their untempered nature, inconsiderate relating, or separation problems.

Classes Start: April 29, 2026

Wednesdays 10:00 – 11:30 AM PT

Runs for 7 weeks

With Jule Epp and Karen Bollman

$250 CAD

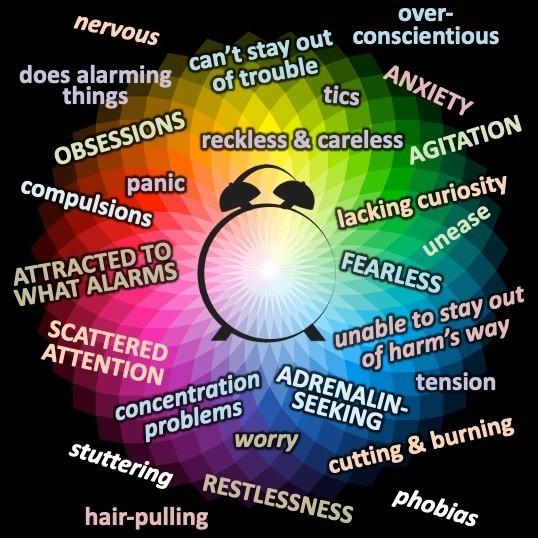

This course provides a fresh look at the causes and consequences of sensory overload in the brain and its role in a spectrum of syndromes, including autism, and to a lesser extent, some forms of giftedness as well as attention problems.

Inquiries

If you have questions or require additional information that you cannot find on our website or FAQ page, you may contact our office on our Inquiries page.

Charity & Non-Profit Status

The Neufeld Institute is a registered Canadian charitable organization under the name Neufeld Institute Foundation and is also registered as a NPO in British Columbia. If you would like to make a contribution to us, please go to our donation page.

Stay Connected with the Neufeld Institute

Sign up for our newsletter to receive insights, editorials, and updates on new courses, webinars, and scheduled classes — all rooted in the Neufeld approach. Whether you're a parent, educator, or professional, our resources are here to help you make sense of the children in your care.