Ralfe Clench was a kind of genius, and a memorable character, whose job was in the administration department at Queenʼs University: he determined the course schedule, by hand, for 2,000 students in the days before computers, and he knew the human face that went with each schedule. He was also the self-appointed (and unofficial) teacher who brought those of us who had not taken Grade 13 calculus in line with our mathematics requirement during first year. He knew what we needed and offered it to us just because he cared.

Ralfe was a tall, plump man with a moon face under a bowl haircut and a Charlie Chaplin mustache who wore the same clothes (or their duplicates) every day, as well as a huge leather utility belt cinched around where his waist used to be. He strode around campus at high speed, and arrived for every class precisely on the last stroke of the starting bell, while declaring the opening statement of the lesson as he entered the room. He lectured until precisely the first stroke of the bell indicating the end of class, at which point he whisked out of the classroom, trench coat flapping behind him, utility belt clanking. He was an unforgettable eccentric, known to all on campus.

These days, Ralfe would probably qualify for various psychiatric diagnoses. He was rigid about his routine, his clothes, his entire life. He was strict about our classroom conduct, including where we sat (he memorized our names on day one, and that was to be our spot for the rest of the year). He was weird too: he lived in a house where all his belongings were filed in grey office file cabinets and his long-suffering wife lived on a different floor; he subsisted on cola drinks and chocolate bars. He was a modest man who did not seek recognition, but most of the rumours that sprang up about him were true. He might have been a nightmare, but he was a kind, whimsical figure, a legend in his time, like a character from a Stephen Leacock story come to life.

We adored him. We learned calculus from him. Instead of feeling coerced into youthful counterwill, we toed the precise lines he drew. Homework was to be handed in each week in correct order, in one format only, folded precisely thus, as part of the “time and motion study” kind of life he lived. He explained that the rituals saved his marking assistant measured minutes per week and ensured we got our correct mark. This assistant came into class at the same time twice a week to collect or distribute homework assignments.

We adored him. We learned calculus from him. Instead of feeling coerced into youthful counterwill, we toed the precise lines he drew. Homework was to be handed in each week in correct order, in one format only, folded precisely thus, as part of the “time and motion study” kind of life he lived. He explained that the rituals saved his marking assistant measured minutes per week and ensured we got our correct mark. This assistant came into class at the same time twice a week to collect or distribute homework assignments.

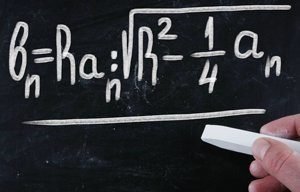

Ralfe was a master teacher. He was able to write calculus examples across the blackboards at the same time as speaking sentences of the theory, a talent I have never seen in anyone else. He sometimes mentioned that he was in a curious position because he was not a university professor. We had no doubt he taught because he adored the subject. He was witty and kind, dramatic and gentle with us, and we felt safe with him. He would call a loud and surprising “hello!” from across the street if he saw one of us outside class, and in the overwhelming days of the bewildering first year, he helped me feel known and appreciated. He even knew what city I had come from, the name of my high school, and my Grade 12 marks.

Oh yes, the utility belt! It was loaded up to contain every tool and item he could possibly need in his daily routine, from pencils to electric drill, chocolate bars to walkie-talkie. One day we locked him out of the room just to see what would happen. We heard him arrive as the last strokes of the class bell chimed. Then a series of clinks and clanks mingled with his usual jolly declaiming of the opening remarks of his lecture. We deduced that he was finding in his belt a variety of tools, which he briskly used to remove the door via the hinges. The door came away, and he laid it against the wall of the corridor, now well into the day’s lecture. Then he walked into the room without pause, said not one word about our trick, presented his entire class without a hitch, and on the stroke of the bell walked out as usual, stopping however to put the door back on its hinges, still locked on the inside. The class erupted. He had not skipped a single beat and never referred to the incident, yet he had an especially brilliant twinkle in his eye for the rest of the day.

While personal subjects and emotions were not in his vocabulary, he knew he was loved by all his flock of students over the years. Many shared personal stories about him in the university journals. His obituary a couple of years ago brought tears to my eyes.

When I was 18, setting off enthusiastically to a university in another province for my first experience of living away from home, I had no idea that what I needed most was a nurturing relationship with my calculus teacher. I never had a real conversation with him and I never sought him out for advice, though heaven knows I needed some, but the warm glimmer in his eye and his shouted “heigh-ho, Liz,” anchored me and kept me safe for a whole school year. It is only now, looking back, that I recognize the truth that the invitation to exist in one adult’s eyes at just the right moment is the very breath of life that gives our puny adolescent wings liftoff. I even got a decent mark in calculus.

Guest Contributor Liz Hatherell is a certified Neufeld Course Facilitator who lives in Winnipeg.